Financing the green economy – a reality check

The need to invest in green initiatives to meet the ambitious net-zero emissions target is clearly recognised by both governments and corporations across the world. According to the World Resource Institute, to date [i.e., as of June 2021] only 59 countries have such net zero targets.

Measures put in place by regulators are facilitating access to capital for such initiatives, and there is evident investor appetite to finance projects with a strong environmental objective.

Investors are also becoming more sophisticated and able to independently assess the real impact of such projects, filtering out greenwashing attempts. According to Giuseppe di Cecio PhD, a Circklo Co-founder, this leaves investors very hopeful that, even though there is a lot to do, things are finally moving in the right direction.

However, as with any new and potentially attractive investment sector, financing the green economy is not without some inherent risks. For instance, the financial risks in investing specifically in green economy are primarily a consequence of ‘green’ business risks.

For instance, a research paper published in Energy Policy in 2020, argues that “retroactive policy changes are costlier in early technology phases when the generation costs differ significantly from market prices.”

Of equal if not higher concern is the fact that, as argued by Marco D’Attanasio PhD, Co-founder of Hadron Capital, “the supply chains in green economy are still underdeveloped, which makes it much harder to scale up a business model efficiently. In turn, this makes financial forecasting and planning difficult, and creates risks that green businesses take longer than expected to achieve their financial targets.”

In other words, green companies are inherently riskier and should be capitalised accordingly.

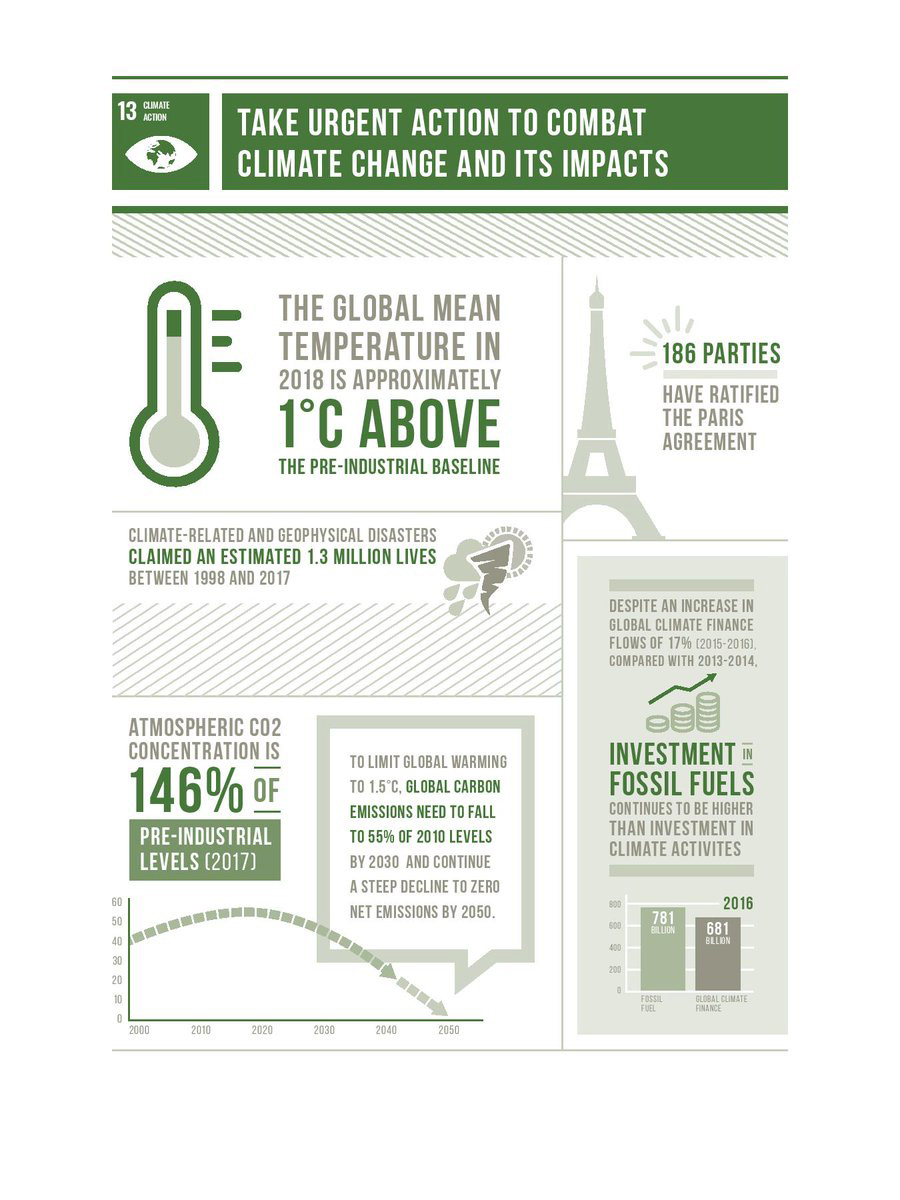

There is no denying that, globally, we are living a climate emergency which will require not just an almost complete reshuffle of traditional business models and types but, also, real behaviour change from all of us: individuals, companies, and governments alike.

Photo credit: UN Climate Change, 2019.

A relatively new term has entered mainstream business conversations: carbon offsetting or carbon credits. Yet, in the view of a growing number of specialists in this area such as Charles Nicholls, the Founder of The Carbon Community, “we cannot offset our way out of this crisis: most carbon offsets do nothing to reduce the CO2 already in the air, and enable those that want to carry on with business as usual to ‘greenwash’, claiming that they are somehow helping the planet.”

In an article published by the World Economic Forum in 2020, the authors argue that one solution available to greenhouse gas emitters are the carbon credits. However, one should seriously question whether paying someone else to either reduce their emissions or capture their carbon, is a viable justification to continue with ‘business as usual’.

How does one use carbon credits to get to carbon-neutral status? If a polluter continues polluting, irrespective of how many paper-based carbon credits it can afford to buy, can we truly consider their activities to be environmentally friendly?

As with most international initiatives and political commitments, the introduction of carbon credits was ratified in the Kyoto Protocol, while the Paris Agreement validated the enforcement of carbon credits, setting out the legal frameworks required to further facilitate the carbon credits markets.

According to an opinion piece published by the Corporate Finance Institute, though carbon credits are beneficial to society, it is not easy for an average investor to start using them as investment vehicles. The certified emissions reductions (CERs) are the only product that can be used as investments in the credits. Today, CERs are sold by special carbon funds established by large financial institutions, thus also allowing small investors to enter the market.

In the complex investment mix of the new green economy, green bonds have also made an appearance. They enable capital-raising and investment for new and existing projects with environmental benefits.

Established in 2014 by a consortium of investment banks composed of Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citi, Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank, JPMorgan Chase, BNP Paribas, Daiwa, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Mizuho Securities, Morgan Stanley, Rabobank and SEB, The Green Bond Principles (GBP) seek to support issuers in financing environmentally sound and sustainable projects that foster a net-zero emissions economy and protect the environment.

For instance, to date The World Bank has raised more than US$13 billion through almost 150 green bonds in 20 currencies, for institutional and retail investors all over the globe.

Photo credit: The World Bank, 2019.

Although green bonds have attracted the attention of the industrial sector and policymakers, the impact of green bond financing on environmental and social sustainability has not been confirmed and, according to the findings of a paper published in 2021 in the Journal of Environmental Management, “there is no empirical evidence on how this financial product can contribute to achieving the goals set out in SDG Agenda 2030.”

There is, perhaps, an even greater cause for caution when it comes to financing the green economy: mis/disinformation and greenwashing. The message from UK’s Financial Conduct Authority Director of Strategy, Richard Monks, couldn’t be clearer:

“It’s crucial that consumers understand the sustainable products they are offered and the differences between them. Particularly as demand continues to grow and new products come to market. As regulators, we need to make sure consumers can trust these products. And that is about giving consumers the right information so they can make informed decisions.

To do this, firms must ensure their communications are ‘clear, fair and not misleading’. What we do not expect to see is firms exaggerating their products green credentials. That’s ‘greenwashing’ and misleads investors.”

For instance, a comprehensive body of research undertaken by Bloomberg in 2021 on the U.S. loans with terms tied to environmental, social and governance targets, identified that these loans have jumped to about $52 billion in volume this year through May 21, a 292% increase compared with all of 2020: “So far, Europe accounts for more than 70% of global ESG-linked loans every year, encouraged by the European Union’s regulations for sustainable financing.”

An analysis of mandates and objectives using the IMF's Central Bank Legislation Database and comparing these to sustainability-related policies central banks have adopted in practice, has been carried out by Dikau and Volz (2021), and its findings have been published in the Journal of Ecological Economics. What comes as a shocking revelation following this research is the fact that, despite the intensive rhetoric on sustainability and green investment used by many governments across the world, “out of 135 central banks, only 12% have explicit sustainability mandates, while 40% are mandated to support the government's policy priorities, which mostly include sustainability goals.”

Where does the rhetoric stop, and actual sustainability-related actions begin?

According to Futures Platform, only two countries in the world are currently carbon neutral or negative: Bhutan and Suriname.

Is it really that easy to achieve a zero-emission target? Or is it much easier to set it and, when it comes to actually achieving it, ‘we can talk about it’? Although the price of clean energy is coming down and the development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies continues, many of the 59 countries who set themselves net-zero targets would need to make significant investments to achieve these within the set time frame.

Fintech development is a novel sector that clearly contributes to the depletion of sulphur dioxide emissions and has a positive impact on environmental protection investment initiatives, according to a paper published in July 2021 in the Environmental Science and EcoTechnology magazine. Its authors posited that “while minimizing the systemic risk fintech poses, policy makers should encourage fintechs to actively participate in environmental protection initiatives that promote green consumption.”

Can financing the green economy be a profitable investment? It certainly can, providing it is done for the right reasons, ensuring a full circularity of commissioned investment, without passing onto another organisation the responsibility to do more, and do better.

Main photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash