Blockchain and the quest for supply chain transparency

Technology can help or hinder, and its use by large corporates can provide clear insights into their commitment to transparency, accountability, and traceability of their entire supply chain: from farm to table, from factory to supermarket shelf.

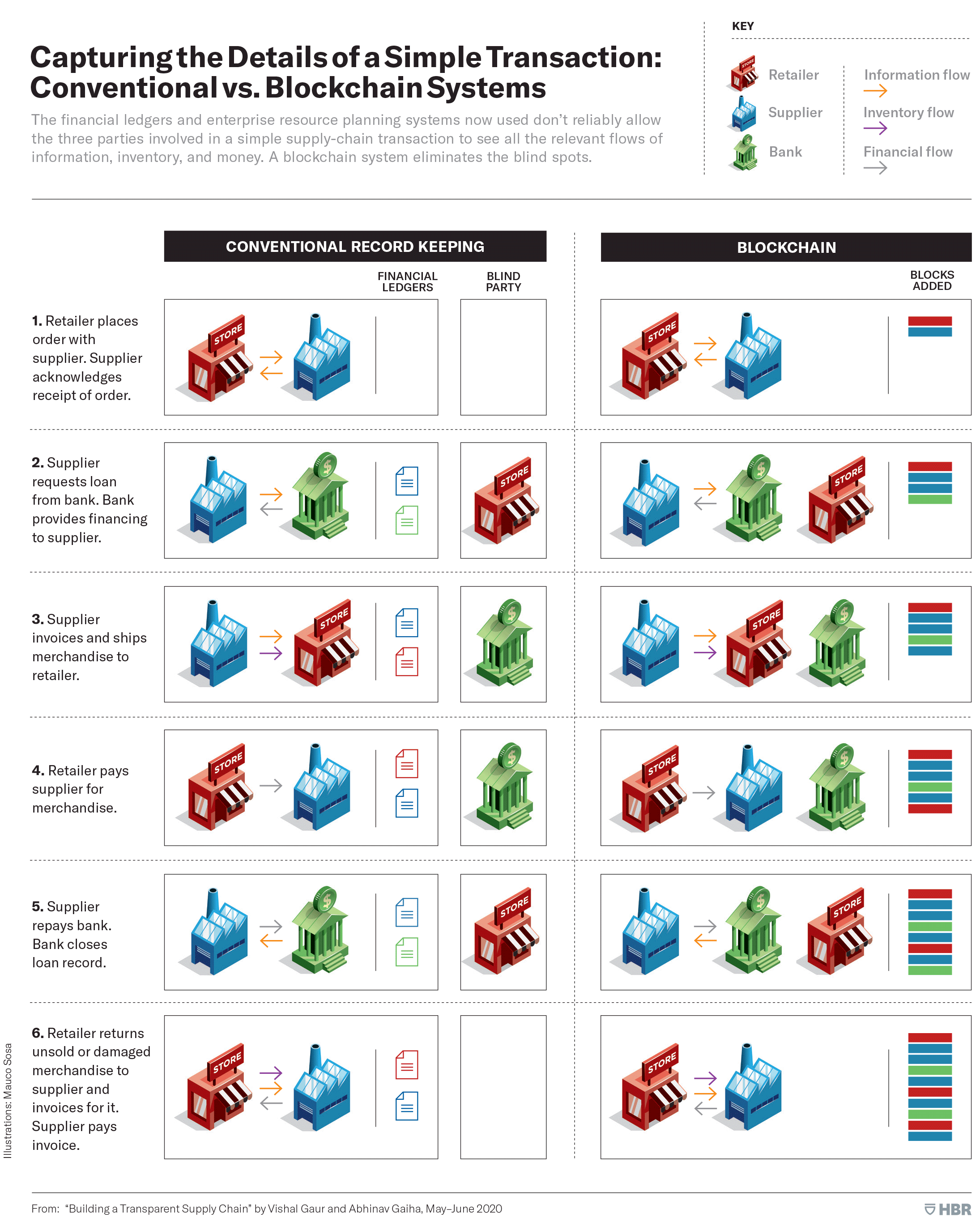

A digital ledger of transactions that is duplicated and distributed across the entire network of computer systems, blockchain technology removes human error and hidden transactions, making it almost impossible to cheat or hack into the system.

In addition to transparency and the much needed environmental and social governance reporting that all respectable corporates should provide today, blockchain technologies achieve much more: they can offer unparalleled insights into the entire chain of operations of any large organisation, identifying lagging times, gaps, deficiencies, and trends within that system.

Image credit: HBR

According to Irannezahd et. al (2021), real-world applications of blockchain technologies in supply chain management face significant challenges, and no deployment of any blockchain system should be commissioned without performing a full, organisation wide, readiness assessment.

However, irrespective of how ready an organisation may be or not to deploy blockchain tech for its supply chain, circularity and abidance by the circular economy principles can hardly be claimed without it: trust, traceability, and transparency emerge as critical factors in designing circular blockchain platforms in supply chains (Centobelli et al., 2021).

In 2020, Forbes published a list with the top 50 users of blockchain technologies across the world, and supply chain management features abundantly across these business mammoths, for instance:

- In Australia, Nestlé used Amazon’s blockchain product to help launch a new coffee brand, “Chain of Origin,” where consumers can look inside the coffee’s supply chain to see at which small farm the beans were planted and where they were roasted.

- BMW has a pilot program with suppliers with plants in Europe, Mexico, and the U.S., and is using blockchain to track materials, components, and parts across its supply chain.

- De Beers’ new software, Tracr, follows diamonds, which have undergone 3-D scans, as the gems are mined, cut, polished, and sold, signalling that the end is in sight for the cruel ‘blood diamond’ trade.

- Dole’s new level of traceability starts on the farm and ends at the grocery aisle, and Walmart customers can now check where their fruit comes from by scanning a code used by farmers.

- Honeywell’s GoDirect Trade platform collects information about aircraft parts over their entire life cycle and makes it available to potential buyers prior to the sale.

- The olive oil giant CHO has been tracking its gourmet Terra DeLyssa oil, helping generate eight data points, including the orchard where the olives were grown, the mill where they were crushed, and the facilities where the oil was filtered, bottled, and distributed, each captured on the blockchain and accessible via a QR code on the bottle.

Above are just some of the examples related to the successful application of blockchain technologies and blockchain marketplaces in supply chain management and its much-coveted transparency.

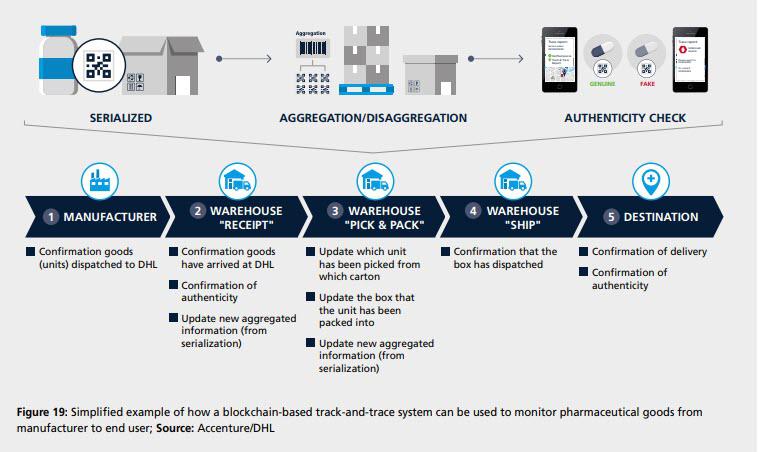

Image credit: Columbus, L. 2019. Top 10 Ways Internet of Things and Blockchain Strengthen Supply Chains. Forbes.

According to Gartner, in 2022 the Supply Chain Management enterprise software market will reach $20.4B, and blockchain’s shared, distributed ledger architecture is becoming a growth catalyst for IoT’s adoption and commercial use in global organisations.

There is, undoubtedly, a significant gap between supply chain transparency and traceability in the developed countries, and the same in the developing countries. While, at first sight, one might be inclined to assume that these are mostly related to fluid legislation and lax regulation – let alone corruption, nepotism, and favouritism – they are mostly related to network reliability and availability.

Kshetri (2021) argues that blockchain’s characteristics are especially important for enforcing sustainability standards in developing countries because these can help address several challenges various stakeholders face in promoting sustainable supply chains in those regions.

In his paper published in the International Journal of Information Management, Kshetri lists the main barriers to blockchain technology implementation in developing countries:

- unfavourable institutional environment,

- high costs,

- technological limitations,

- unequal power distribution among supply chain partners, and

- porosity and opacity of value delivery networks.

Despite the extensive literature on Blockchain, in recent years no clear framework has defined – or has been agreed on - whether a supply chain should implement blockchain or not, according to a research paper published by Aslam et al. (2021) in the Journal of Innovation & Knowledge.

The interrelation between information confidentiality, usability, traceability, transparency, and optimisation requires various visibility layers, and the data feeding into the system needs to be as accurate and as timely as possible.

Blockchain is, without a doubt, a major step towards streamlining operations and improving operational performance. Its integration, albeit often seamless, is as dependent on a myriad of variables as it is on the IT systems/marketplaces it uses.

Is this the right time to create the architecture of a blockchain-based sustainable supply chain visibility management platform, centred on context-awareness? One that is secure, auditable, and mutually benefiting sustainable supply chain information sharing, in heterogeneous context-aware scenarios, whilst recognising the underlying characteristics of sustainable supply chain visibility? Sunmola (2021) believes it is.

With many documents involved in supply chain management, the risk of fraud and forgery increases. Given the large number of stakeholders in logistics chains, the level of transparency is often lost (Cerny, 2021) and the much needed accountability of sources, process, means and methods becomes utopic.

There is much more to a product than its provenance and the process stages it goes through to reach its destination: forced labour, working conditions, human trafficking, banned or illegal substances, use of unauthorised substances and so much more.

No organisation, large or small, can claim its operations are in full compliance with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, or with the circular economy principles, unless it can track and trace its entire supply chain system.