A national strategy for artificial intelligence (AI)

The UK Government has recently published its “National AI Strategy”, a lengthy document, peppered with lofty aspirations and rallying statements such as supporting “the transition to an AI-enabled economy” and ensuring that “the UK gets the national and international governance of AI technologies right to encourage innovation, investment, and protect the public and our fundamental values”.

And paramount to achieving all these objectives is the public’s “trust and support,” and the “involvement of the diverse talents and views of society.”

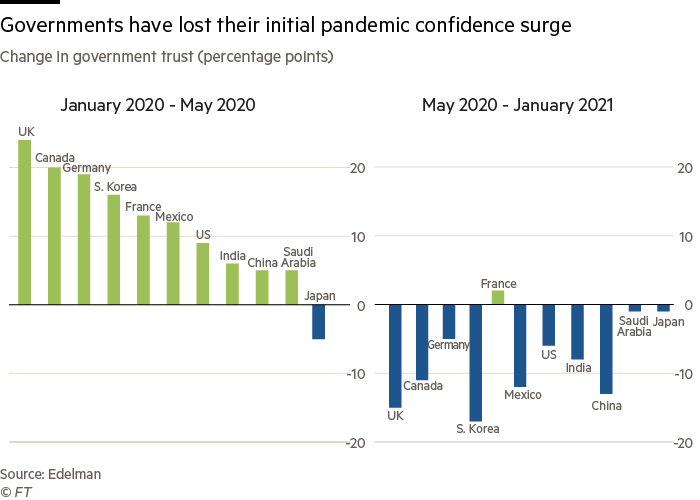

A natural question to ask would be related to the public’s trust in what and support of whom, since trust is related to reliability and competence, and support is dependent on any one’s government ability to deliver on its various commitments made to its voters.

Image credit: Edgecliffe-Johnson, A. 2021. Trust in governments slides as pandemic drags on. Financial Times.

To date, and according to OECD’s latest data, there are over 600 AI policy initiatives from 60 countries, territories, and the European Union.

There is a remarkable two-part document entitled Comparison of National Strategies to Promote Artificial Intelligence published by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation which asks two very fundamental questions:

- What regulatory framework conditions have they [Governments] defined?

- How do they [Governments] implement policy strategies and programs to create new industrial policy facts?

Artificial intelligence should not be used as a component of political rhetoric and electoral promises – it needs facts, significant amount of support and investment from the private sector, and an apolitical Ombudsman/Regulator to ensure the lack of vested interests of any party – be it government or private sector – in the development and deployment of any AI:

“If you run a business – whether it is a startup, SME or a large corporate – the government wants you to have access to the people, knowledge and infrastructure you need to get your business ahead of the transformational change AI will bring, making the UK a globally competitive, AI-first economy which benefits every region and sector.”

Excerpt from UK’s National AI Strategy

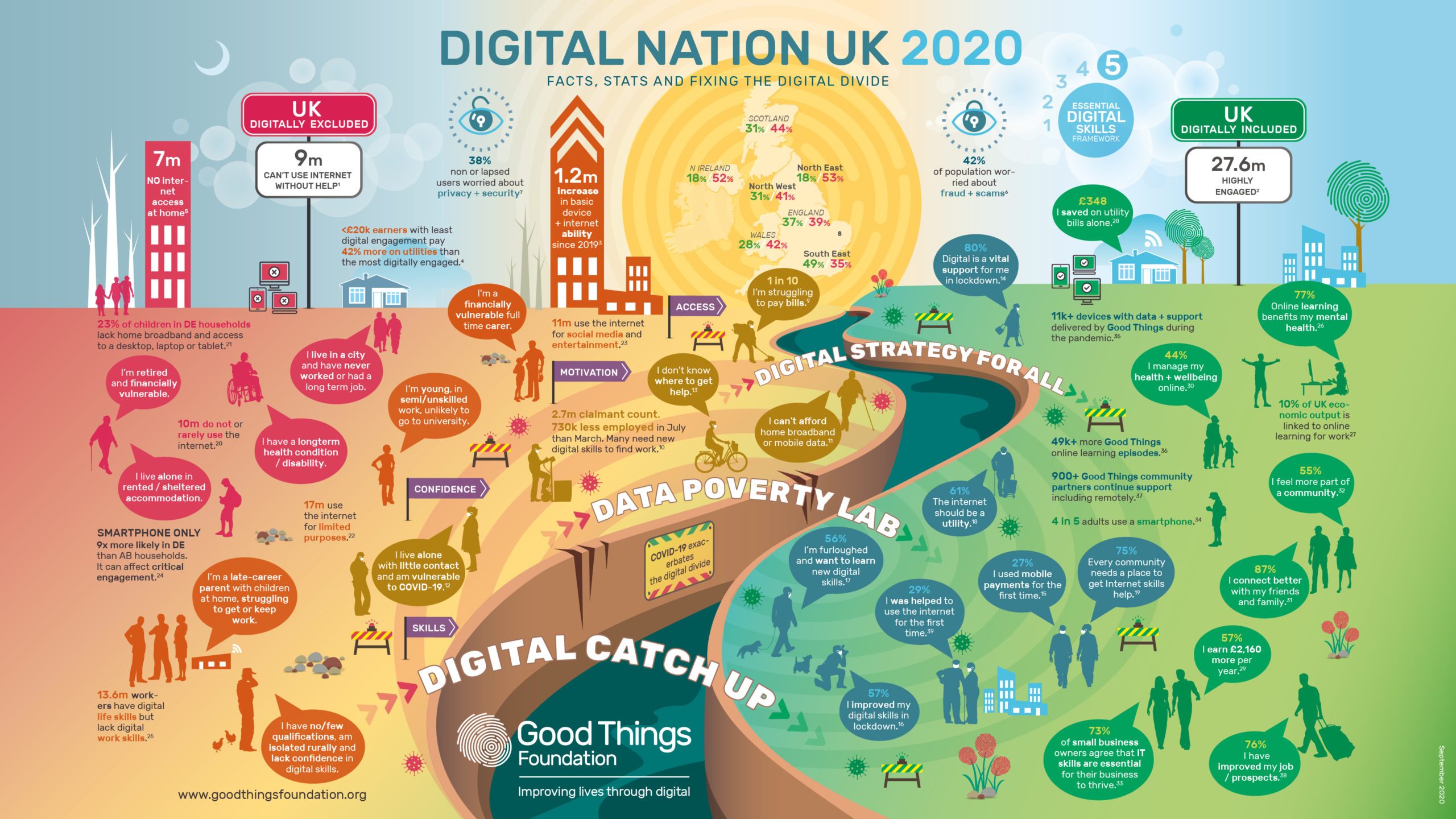

To enable AI driven technologies, to foster a truly inclusive ecosystem – one solely driven by innovation and collaboration – the digital divide currently existent in the UK, let alone the digital poverty that faces many of the country’s youths and adults needs to be rapidly narrowed, as this infographic courtesy of University of Liverpool demonstrates:

GMCA pushes to be “100% digitally enabled” after research highlights region’s digitally excluded. University of Liverpool. 2020.

Image credit: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org

As of 2020, “2,500 new Masters conversion courses in AI and data science are now being delivered across universities in England”. According to Statista, “the 2019/20 academic year, there were over 412,000 enrolments for courses involving business and management studies, making it the most popular subject group in that year. Subjects allied to medicine had over 295,000 enrolments making it the second-most popular course in that year”.

According to UCAS data cited by www.fenews.com, acceptances to computer science courses have risen by almost 50% (from 20,420 in 2011 to 30,090 in 2020); and acceptances to engineering courses are up 21% from 25,995 in 2011 to 31,545 in 2020 – driven by an increase in demand from UK 18 year olds; whilst acceptances to the newer artificial intelligence (AI) courses have seen a 400% rise in the past decade (from just 65 in 2011 to 355 in 2020) – there is a stark difference between AI courses uptake and business studies and medicine uptake (over 700,000).

Any national artificial intelligence strategy should include clear economic goals and benchmarks – visa benefits for high skilled migrants and government-led investments are a form a state-aid given to either employers of such non-native talent or to various businesses to catapult their innovation potential. To date, and according to Konrad Adenauer Foundation, “the Chinese strategy is the only one of that contains measurable economic goals and benchmarks.”

The most valuable Top 20 technology companies as of May 2018. Comparison of National Strategies to Promote Artificial Intelligence.

Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2019, p. 58.

The ranking above clearly demonstrates that the technological competition is clearly between the US and China, with each country operating a different incentivisation system: the US’ one is based on private sector co-operation and start-up acceleration, meanwhile the Chines one is state-controlled and state-driven.

There is much more at stake in the race to AI/computing supremacy that is currently being fought between the world’s superpowers: the AI’s ecosystem ability to serve and protect humanity, to improve the sustainability and circularity of our interrelated and co-dependent economic systems, and to offer clear incentives for human innovation in all fields.

To achieve these, and to monetise all traditional competitive advantages available to nation states, competition becomes moot; collaboration and ecosystems become paramount.