Food, hunger and waste

According to Action Against Hunger, one in nine people are hungry or undernourished, globally. Although the food produced across the world is more than enough to feed the entire global population, more than 810 million people still go to bed hungry every night.

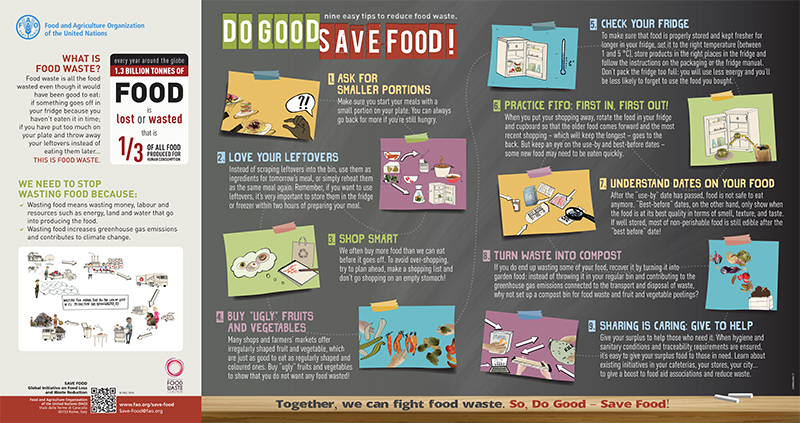

United Nations’ Environmental Programme (UNEP) Food Waste Index Report 2021 presents some stark findings: food waste from households, retail establishments and the food service industry totals 931 million tonnes each year. Nearly 570 million tonnes of this waste i.e., almost 60%, is household food waste.

What is even more shocking is that, according to UNEP’s Executive Director, Inger Andersen, “if food loss and waste were a country, it would be the third biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions.”

The availability and diversity of food and food sources have been, for a very long time now, taken for granted in the Western countries and developed economies around the world although, ironically, in the UK there are over 2,200 food banks (the US’ equivalent of food pantries) and in the USA over 200 food banks and 60,000 food pantries.

The food waste chain is complex and, one could argue, our attitude to food and how we waste it can be traced back to our childhoods and our learned behaviours: if food were aplenty and easy to come by, it was easily discounted and thus even more easily discarded. The opposite is true: if food were scarce, and its diversity limited, the respect for its source and availability would be much higher.

Attiq et al (2021) argue that in the United States about 30–40% of the food supply remains uneaten, representing $160 billion in economic losses. Furthermore, the average U.S. household wastes 31.9% of their food, at a cost of $1,866 per household annually or an annual cost of $240 billion nationwide.

In a recent interview for Wired Retail, Maria Morais – Consumer Industries Cloud Director at SAP, and Circklo Chairwoman – gave a very interesting and insightful snapshot of responsible design and production of consumer-packaged goods, with particular emphasis on the circular economy approach to food waste:

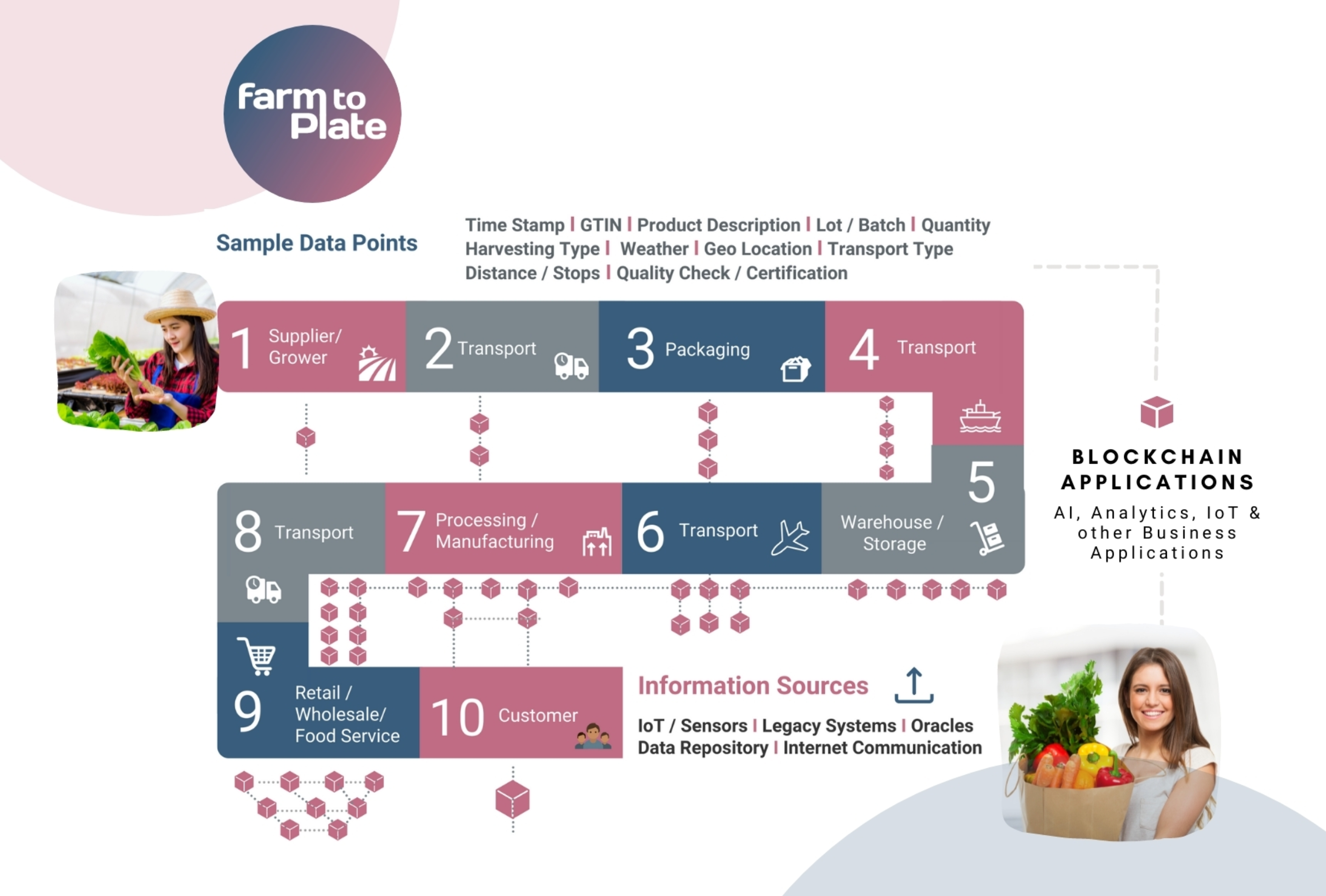

In a recent survey carried out in 2020 by Transparent Path, a US-based start-up bringing together the technology to protect high-value perishable foods for supply chain visibility, shoppers were asked to describe (and even justify) their ethical food choices, such as the credibility and trustworthiness of the information related to the food they are buying, the importance of organic certification, the importance of ‘quality’ and the steps/journey the food takes from source to table and, most importantly, the safety of the food they buy.

The main conclusion of the survey was, and should be, a revelation for both retailers and their suppliers:

“Shoppers are hungry for more information about how their food is raised or grown – and they are willing to pay more for products that provided this information.”

Both Morais and Transparent Path, as well as many other organisations address the circularity of the entire food system and offer clear solutions or steps forward, but there is one significant mountain to climb: the retailers’ willingness to be fully transparent, and the customers’ willingness to waste less.

Brand images are often based on myth, on concerted efforts to present an image that does not have a strong foundation in their actual business practices. And the application of behavioural science techniques and principles in the advertising industry – which plays a massive role in consumers’ purchase decisions – is the key driver in generating demand for a particular brand or product of a brand.

Transparency in the food supply chain goes beyond sweatshops and child labour: it is about animal and crop welfare, about storage and freight conditions, about perishability and traceability.

Image source: Business Wire, 2021

For instance:

- KFC admitted to poor welfare conditions among its UK chicken suppliers, with more than a third of the birds on its supplier farms in the UK and Ireland suffering from footpad dermatitis;

- A lab study commissioned by The New York Times has unearthed no traces of tuna DNA in the tuna fish that was collected from Subway stores and sold as tuna sub;

- At least 95,000 male calves – most of them only days old - are killed on-farm yearly in the UK because it costs the farmers more to rear them than to kill them: ‘shooting the calf costs as little as £9, including the cost of the knackerman who will incinerate the body or, in some cases, send it to kennels to be turned into dog food’. Yet, the labels on the milk bottles sold in supermarkets never tell consumers that a male calf was slaughtered so we can have it with cereal for breakfast or pour it in our tea and coffee.

- Agricultural experts warned as far back as 2009 that the plan to develop a dicamba-tolerant system – developed by Monsanto and Basf - could have catastrophic consequences for many American farmers’ crops. According to The Guardian, ‘several million acres of crops have now been reported to be damaged by dicamba, according to industry estimates. And more than 100 US farmers are engaged in litigation in federal court alleging Monsanto and BASF collaboration created a “defective” crop system that has damaged orchards, gardens and organic and non-organic farm fields in multiple states.’

And these are just some of the myriads of examples out there related to food transparency, food circularity and food waste. To date, only a handful of countries around the world, UK being one of those, have composting facilities for organic (food) waste, reintroducing it directly into the food chain circuit.

Perhaps the most important lessons of this article, or its most important takeaways, should be these two questions:

Does the food industry need to produce that much food? And if it doesn’t, then why does it continue doing it anyway?