Do you really want to check your supply chain?

There is, undoubtedly, a significant gap between supply chain transparency and traceability in the developed countries, and its transparency and traceability in the developing countries.

While at first one might be inclined to assume that this gap is mostly related to fluid legislation and lax regulation – let alone corruption, nepotism, and favouritism – this gap is mostly related to supply network reliability and availability.

Africa’s population is close to reaching 1.4 billion, and the median age in Africa was 19.7 years as of 2020. In practical terms, these statistics translate into a huge market potential, great business opportunities, a very young population and a mostly untapped human and resource potential.

The African continent is made up of 54 sovereign states, with varying degrees of infrastructure development and GDP – with Nigeria being the richest and most developed African nation, and The Central African Republic being the poorest. It should also be noted that 22 African countries are in the top 25 poorest countries in the world.

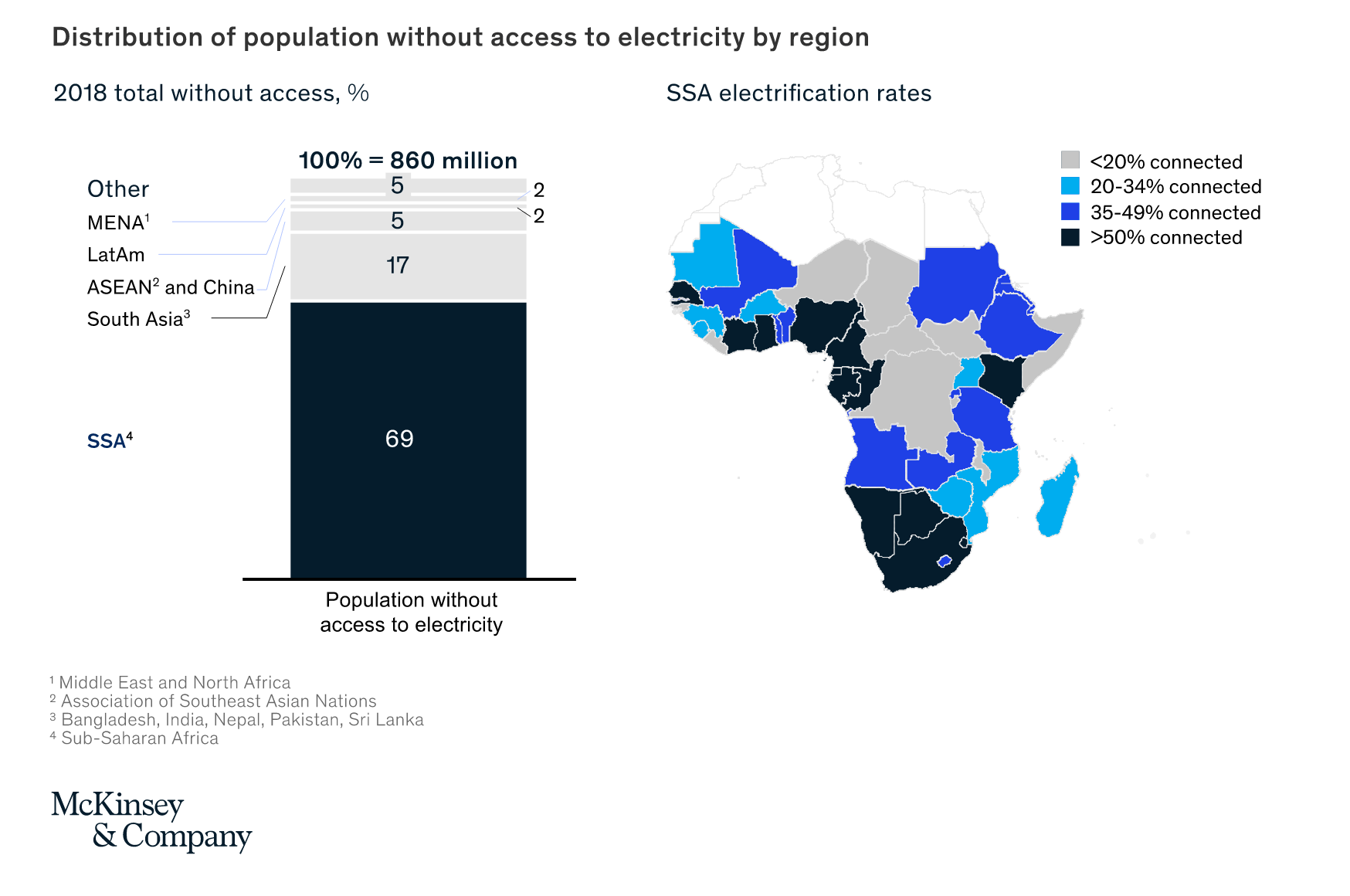

In terms of basic infrastructure such as roads, sewage, water and electricity supply, the African continent’s ability to provide for a rapidly growing population has never been possible, and the pressure on national infrastructures is close to reaching its tipping point.

For instance, electricity is not a given, but a luxury:

As in other parts of the world, political economy issues can impede infrastructure development in Africa. In particular, disputes arising from the political process as well as the expression of vested interests by politicians or businesses take time to resolve. Moreover, changes in political leadership can overturn previous commitments to infrastructure projects.

About one-third of Latin America's roughly 600 million residents live in poverty, or in what the United Nations defines as extreme poverty: subsisting on less than $1.90 a day. Brazil is, by far, the Latin American country with the highest GDP (USD 1,434 billion) and Honduras has the lowest GDP (23.69 billion).

It is very interesting to note that, compared to the African continent’s median age of 19, that of Latin America is 31 – almost 60% higher – and so is Latin America’s life expectancy (82 compared to Africa’s 66).

More than 60% of Latin America’s roads are unpaved, compared with 46% in emerging economies in Asia and 17% in Europe. Two-thirds of sewage is untreated. Poor sanitation and lack of clean water are the second-biggest killer of children under five years old, according to the World Health Organisation. Losses of electricity from transmission and distribution networks are among the highest in the world. Latin America spends a smaller share of GDP on infrastructure than any other region except sub-Saharan Africa.

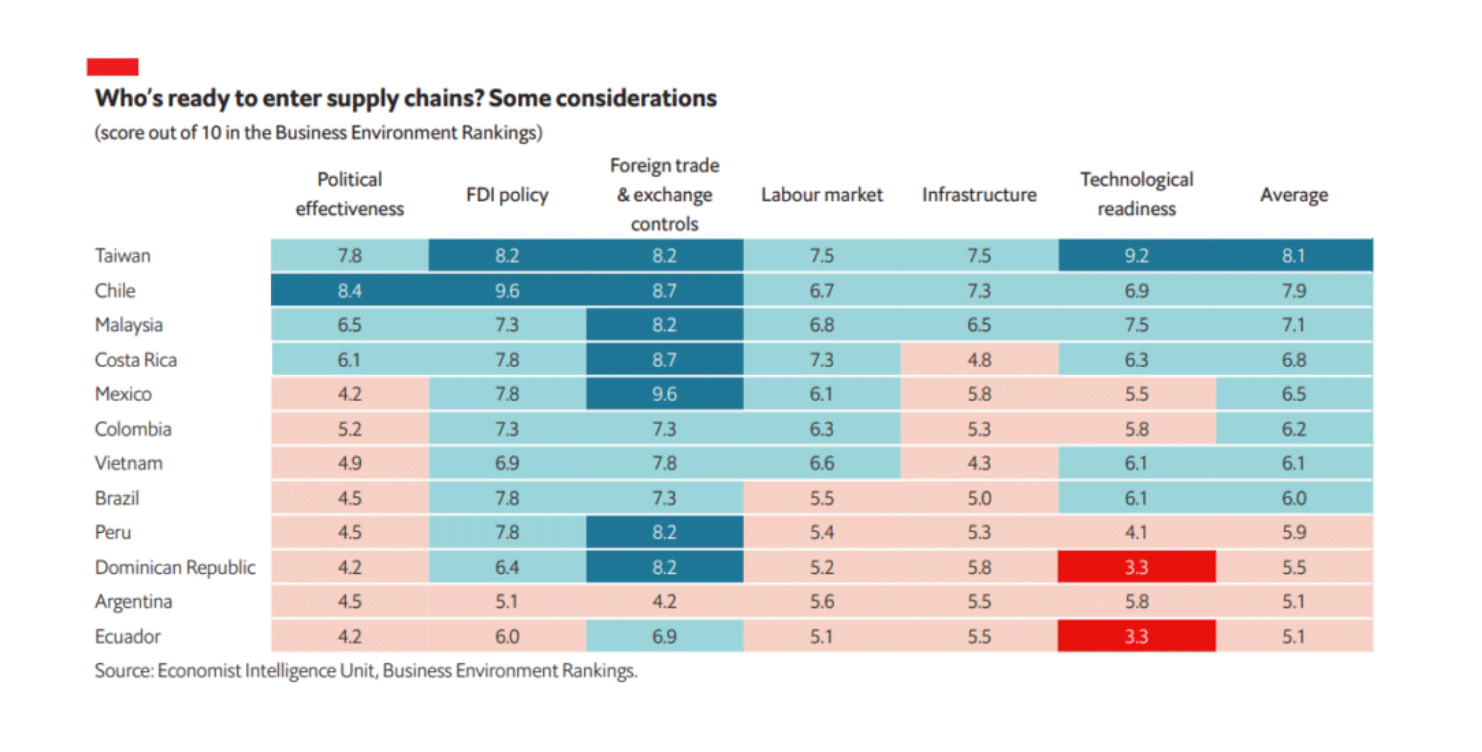

And, according to The Economist’s Intelligence Unit, the Latin American countries will find it very difficult to enter the supply chain race:

Countries may be classified as either developed or developing based on the gross domestic product (GDP) or gross national income (GNI) per capita, their level of industrialisation, the general standard of living, and the amount of technological infrastructure. It’s noteworthy that, in 2020, the UN has classified 126 countries as ‘developing’: these are most often countries with a lower income, an underdeveloped industrial base, a lower standard of living, and a lack of access to modern technology. As a result, developing nations frequently experience a lack of jobs, food, clean drinking water, education, healthcare, and housing.

One of the most important aspects related to supply chain optimisation in developing economies is the verification (audit) of each loop in the chain: from what goes into the ground (in case of agriculture) to the moment it reaches one’s dinner table. Supply chain issues should address much more than the transparency of the timeline offered by blockchain use; they should also analyse the processes deployed and the solutions (often ad-hoc) identified to fix a foreseen problem.

One of the most daunting issues in supply chain optimisation and actual application (and verification) of any and all SDG goals or ESG principles in developing economies is the workforce, particularly the use of child labour.

In 2020, Channel 4 News (UK Network) aired an undercover documentary about Nespresso’s and Starbucks’ coffee farms in Guatemala. It was, and still is, a chilling wake-up call for all large multinationals keen to signpost their ESG achievements and commitments, yet not so keen in actually putting boots on the ground and verifying who grows their products or provides their services:

Nespresso visits its Guatemala farms once a year, and Starbucks once every 2-4 years. Their visits are announced so there are no surprises, in other words plenty of time for the farmers to ‘hide the children’ since child labour, especially for children under the age of 12 is illegal irrespective of economic classification (developed or developing) of any country in the world.

But is this entirely Nespresso’s and Starbucks’ fault? Or the ‘fault’ of many other multinationals just like them? Are they the only ones to blame? When a family cannot afford to feed itself, should children work because, otherwise, they and their parents would starve?

It is very easy to claim (and even believe) that what multi-billion dollar/pound corporations are doing is good – one only needs to look at Oxfam and the constant stream of sexual abuse claims coming in their direction from the Caribbean and Africa.

Technology and digital advancements are a fantastic means of keeping track, in real time, of where a product is, which company made it, which carrier brings it over and how it was made. But supply chains in developing economies (and not only), start with people: and technology can take us only that far without spot checks (ad-hoc audits).

Children have been used as labour from times immemorial; and they still are, even in developed economies, mostly in rural settings. Most multi-national organisations believe that local/societal cultures will welcome them with open arms, grateful to them for the jobs and opportunities created, and that they will definitely read the entire suite of corporate manuals, best practice guidelines, anti-bribery and anti-corruption policies, and so on.

The question we ask you, the reader, is relatively easy, but the task is very difficult: are you ready to ‘walk’ your supply chain?